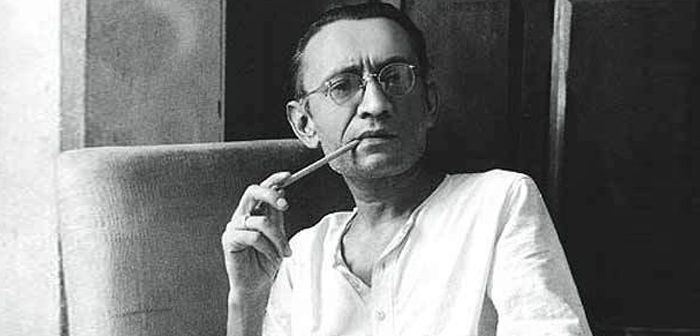

In the summer of 2025, I offered a course titled Manto Naama at Habib University, a name I deliberately chose over the more explanatory “Why Manto”, to stay true to the spirit of poetic ambiguity and critical inquiry that Saadat Hasan Manto’s life and work demand. The course was intellectually rigorous, emotionally charged, and profoundly urgent in its scope, aiming also to reconnect students to a writer who spoke the same language as them. It wasn’t just a literature class; it was a conversation about ethics, identity, trauma, desire, and resistance.

Designing this course was as much an academic exercise as it was a deeply personal journey. I had taught Manto’s short stories before in different contexts, but I had never dedicated an entire semester to him. Why now? Why Manto?

The answer came from a combination of literary necessity and political relevance. We live in a time when questions of truth, freedom of expression, gendered violence, and national identity are no longer confined to scholarly discourse, they seep into our everyday lives. Manto, who lived and wrote during the chaos of Partition, remains one of the few voices in South Asian literature who consistently wrote against the grain. He wrote about prostitutes, madmen, murderers, refugees, and failed lovers, not to sensationalize them, but to hold up a mirror to a society that preferred to look away. Manto’s writing was a wakeup call, demanding readers to have more daring conversations, to think more conscientiously.

When I sat down to design the course, I knew I wanted to resist the trap of nostalgia. Manto is not a writer we admire from a distance. He is one that unsettles us, provokes us, demands accountability. My pedagogical intention was to bring Manto closer to the students, not just as a historical figure, but as someone whose struggles were local to the subcontinent, someone whose work continues to speak to the present. I wanted students to read him not only through the lens of Partition Studies or Urdu literary history, but also through ethics, trauma theory, gender and sexuality studies, and postcolonial critique.

The course began with foundational questions: What is literature? What is truth? Is fiction obliged to comfort or to confront? These inquiries helped set the tone for our approach to Manto’s works. We read stories like Toba Tek Singh, Thanda Gosht, Khol Do, Hatak, Kali Shalwar, and Dus Rupay, along with lesser-known sketches and critical essays. We also read commentaries by Ayesha Jalal, Muhammad Hasan Askari, Veena Das, and others, to deepen our engagement with the themes of censorship, madness, memory, and marginality.

One of the most memorable moments in the classroom occurred during our close reading of Toba Tek Singh. A student paused and asked: “Is Bishan Singh mad because of Partition, or does Partition expose the madness that already existed in the logic of borders?” That single question sparked an intense discussion about cartography, trauma, and the absurdities of nationhood. It is precisely this kind of reflective, rigorous questioning that I hoped the course would encourage.

Another unforgettable session focused on Manto’s essay Main Afsana Kyun Likhta Hoon (Why I Write Short Stories), in which he defends his work that is perceived as “obscenity” by arguing that if society is obscene, literature must not look away. In this session, students were divided into small groups in which they responded to the essay with textual analysis, personal reflections, performances and artwork. Some spoke about the silence of survivors in their own families; others connected Manto’s critique of respectability politics to present-day gender norms and digital shaming. The classroom was not a neutral space, it became, in Manto’s words, “a court of conscience.”

Throughout the semester, I encouraged students to read beyond the text. What are the silences in a Manto story? Who speaks, and who remains voiceless? What does the city of Lahore, or the body of a woman, mean in Manto’s imagination? How does he write about men who are broken, complicit, or powerless? These were not rhetorical questions, they formed the scaffolding for our critical essays, presentations, and in-class writing assignments.

As part of the course’s final project, students presented research papers in a conference-style session. Their topics ranged from the aesthetics of disgust in Boo, to Manto’s critique of nationalist masculinity in Mozel, to the structural violence encoded in bureaucratic language in Naya Qanoon. It was inspiring to see how each student found their own way into Manto’s work—some through rage, some through grief, some through sheer curiosity.

The broader relevance of teaching Manto today cannot be overstated. In a time when critical thinking is under siege, when literature is policed for ideological purity, when dissent is mistaken for treason, and when empathy is considered radical, Manto’s writing offers not just content, but also method. He teaches us how to see. His stories do not merely describe violence—they force us to confront with our complicity, our indifference and our voyeurism.

At Habib University, where our Liberal Core emphasizes critical inquiry, transdisciplinary thinking, and ethical reasoning, a course like Manto Naama finds fertile ground. It brings together students from varying Programs into a shared space of questioning. The course contributes not only to the academic goals of the Comparative Humanities program but also to the intellectual and emotional growth of students as young thinkers navigating an often-confusing world.

For me as an instructor, Manto Naama reaffirmed the power of literature to disquiet, to illuminate, and ultimately to transform. In every session, I was reminded that teaching is not just about transferring knowledge, it is about inviting others to join in a dialogue that transcends time, geography, and ideology. And who better than Manto to anchor such a dialogue?

About the Writer:

Inamullah Nadeem is a poet, writer, translator, and Ph.D. candidate in Literature at Federal Urdu University, Karachi. He has taught at Habib University since 2015, leading courses in Urdu and Punjabi literature, including the award-winning Jehan-e-Urdu. With over 10 published books and essays featured in major literary journals, Mr. Nadeem is a prominent voice in Pakistan’s literary circles. He regularly speaks at national festivals and brings deep expertise in creative arts, language, and pedagogy to his teaching and writing.