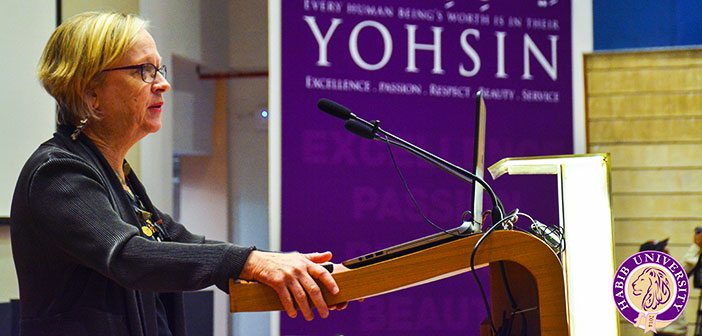

Speaking at Habib University’s annual Yohsin Lecture, Dr. Deborah K. Fitzgerald explained how the arts, humanities and social sciences have helped MIT maintain its dominance in science and engineering

HABIB UNIVERSITY, November 23, 2015: In recent years, there has been a great international debate on what kind of college education best prepares students for the world we live in today. The emergence of the digital economy, globalization, domineering financial institutions, and the ever-presence of computers has created a belief that students should be concentrating on so-called STEM fields – Science, Technology, Engineering, and Medicine. Indeed, in many countries it is difficult to find alternatives to this kind of education. However, most of the pre-eminent educational institutions of the world take the contrarian view, requiring their students to dedicate a considerable portion of their time to liberal arts courses along with their chosen STEM majors.

The annual Yohsin Lecture hosted here at Habib University on November 23 was centered on this debate. It was delivered by Dr. Deborah K. Fitzgerald from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to an audience of well over 700 businessmen, philanthropists, scholars, students and parents, as well as the Habib community.

Dr. Deborah Fitzgerald is a Professor of the History of Technology, in the Program in Science, Technology, and Society at MIT. She is also the former Kenan Sahin Dean of the MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (2006-2015). She received her B.A. from Iowa State University (History and English, 1978) and her Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania (History and Sociology of Science, 1985). Prior to joining the MIT faculty in 1988, she was an Assistant Professor in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University.

In her talk, Dr. Fitzgerald took the position that the most pressing and complicated problems we face in the world today will not be solved by STEM alone. Entrenched warfare, climate change, poverty, discrimination, clean water, adequate employment and disease are fundamentally human problems, and STEM alone cannot offer lasting solutions for them. She underlined the importance of a rigorous liberal arts education that can teach students how to deal with these human problems, and become the leaders we need in the days ahead. To make her point, she described how a pre-eminent institution like MIT has remained committed to the humanities while still maintaining its technical leadership.

Over the course of the lecture, Dr. Fitzgerald acknowledged that many, if not most, educational systems are focused more on providing students vocational skills, not the ability to solve problems in generals; on helping students get jobs, not teaching them how to lead their lives. She explained how this leads to problems down the road: during her travels to South Korea (a global leader in technology), she was asked repeatedly to prescribe a reorientation strategy for the country’s higher education systems, which felt that though they were “technologically superior” than the US, they could not produce leaders “like Steve Jobs”. Dr. Fitzgerald explained that the concern was that South Korea’s universities weren’t creating enough graduates that could think out of the box – or those who were willing and able to take on the “messy” reality of human existence. These features are hallmarks of students who have been nurtured with a strong liberal arts education, she said.

She explained that MIT’s openness to the liberal arts initially came from a desire to produce science and engineering graduates who would be gentlemen, not people “who emulate mechanics”. Over time, the need for liberal arts evolved as educationists realized that the really tough problems they needed to prepare graduates for were human/social problems. Explaining this relationship between humanities and science further, she added: “Humanities enable us to understand how human beings will use and abuse the powerful new technologies that are to be introduced in the next few decades.”

The audience took advantage of Dr. Fitzgerald’s considerable experience as an educationist at a top global university to ask her deep and cutting questions regarding the scope and applicability of the liberal arts to the Pakistani context. A few members of the audience expressed their frustration at the kind of workers that came to them for jobs. They admitted that though their prime concern was to hire employees who were technically sound, they were deeply dissatisfied with the general quality of individuals they ended up hiring.

The Yohsin Lecture brings the most distinguished scholars, artists and critics of our time to Habib University for engagement with civil society and the University’s faculty and students. It is administered by either of the Habib University’s two schools and academic centers, depending on the nature of talk and the invited guest.