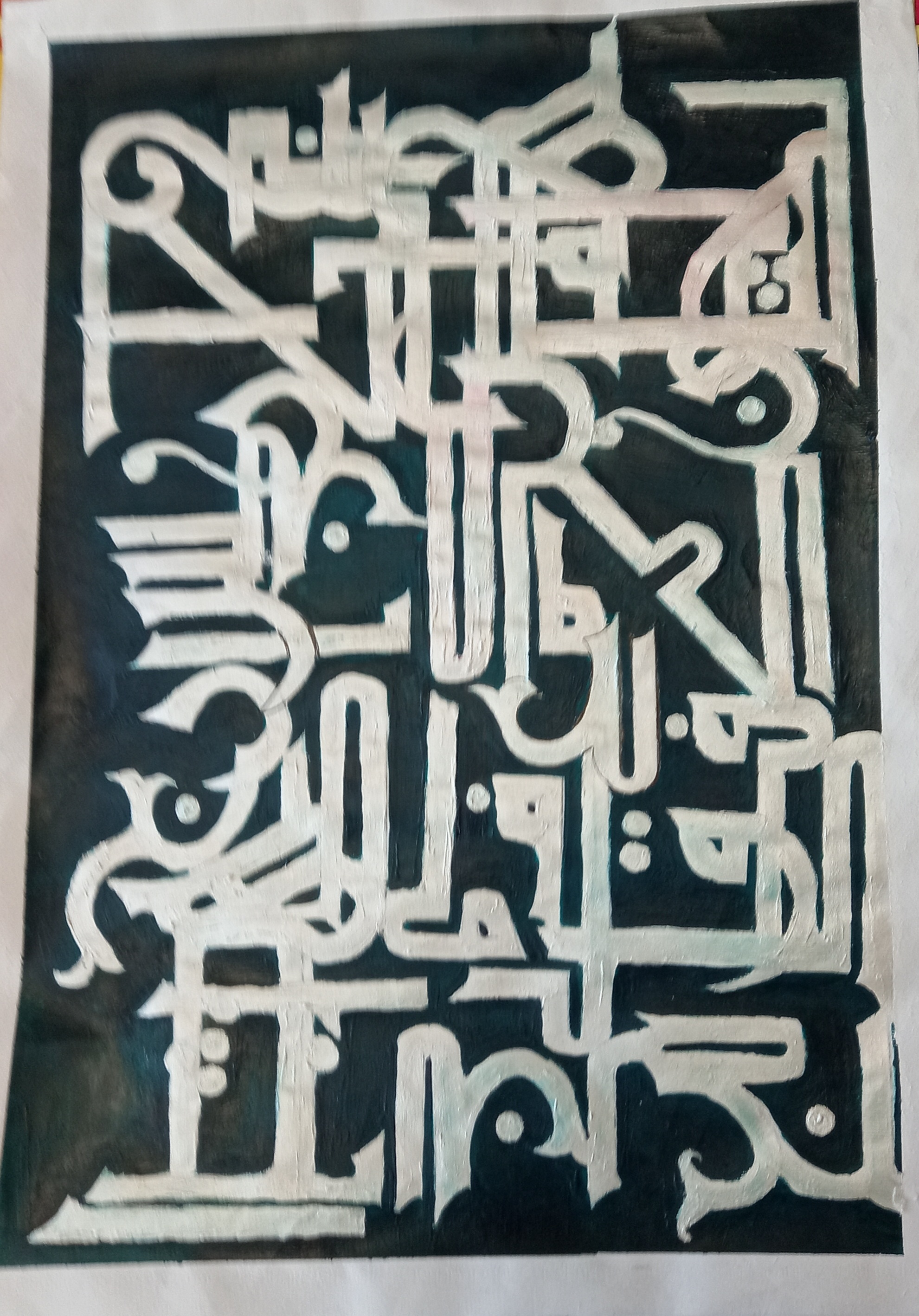

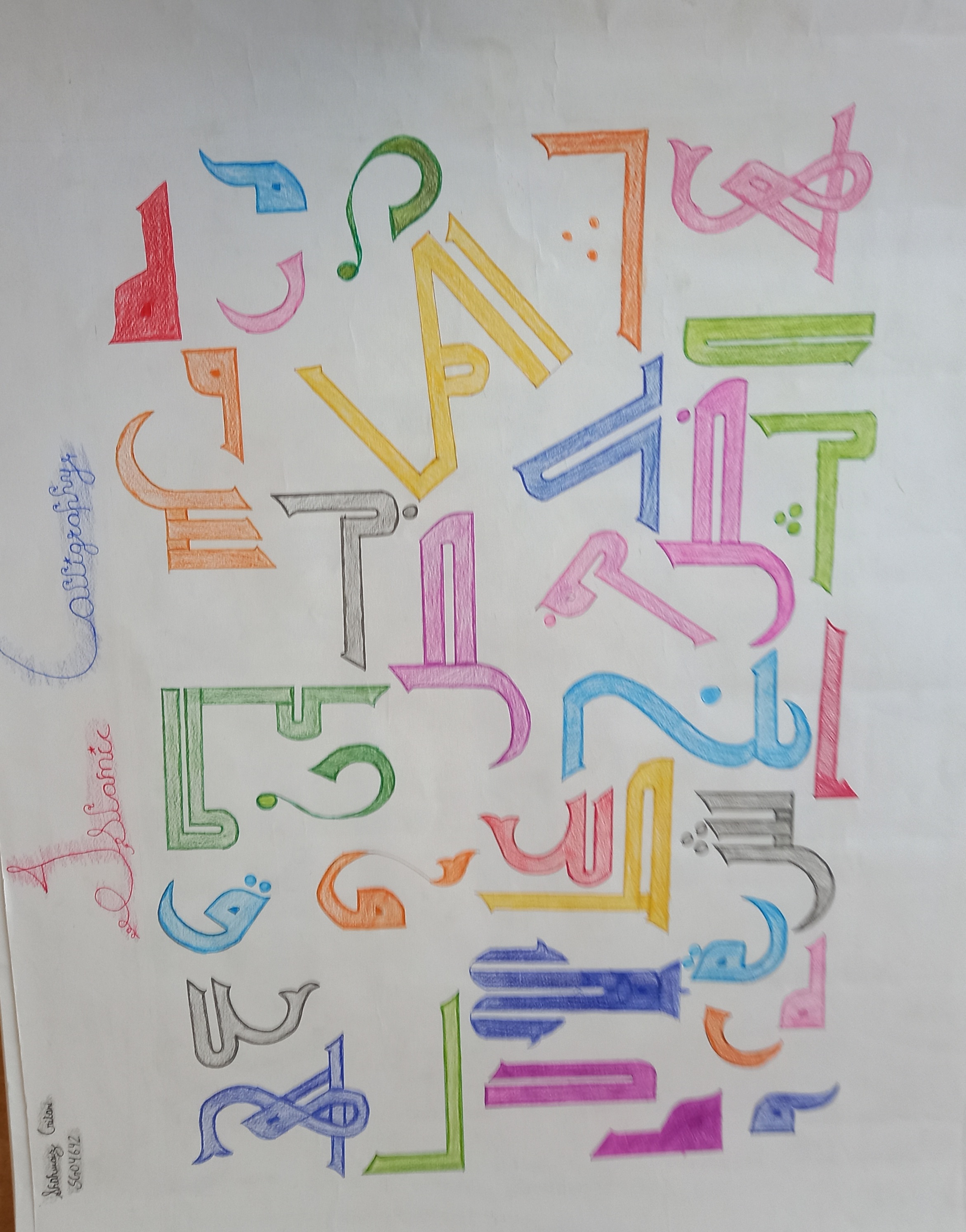

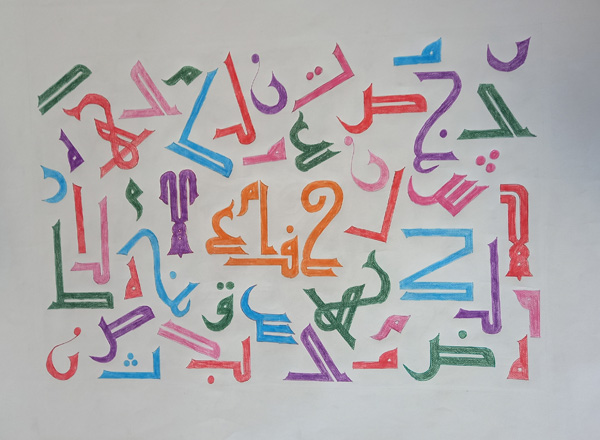

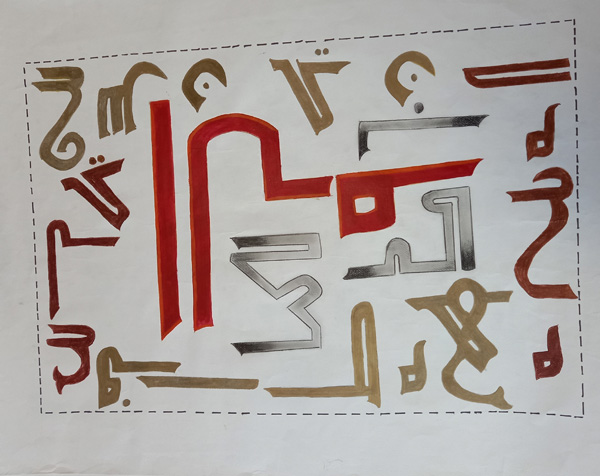

Divine Proportions: Introduction to Islamic Calligraphy

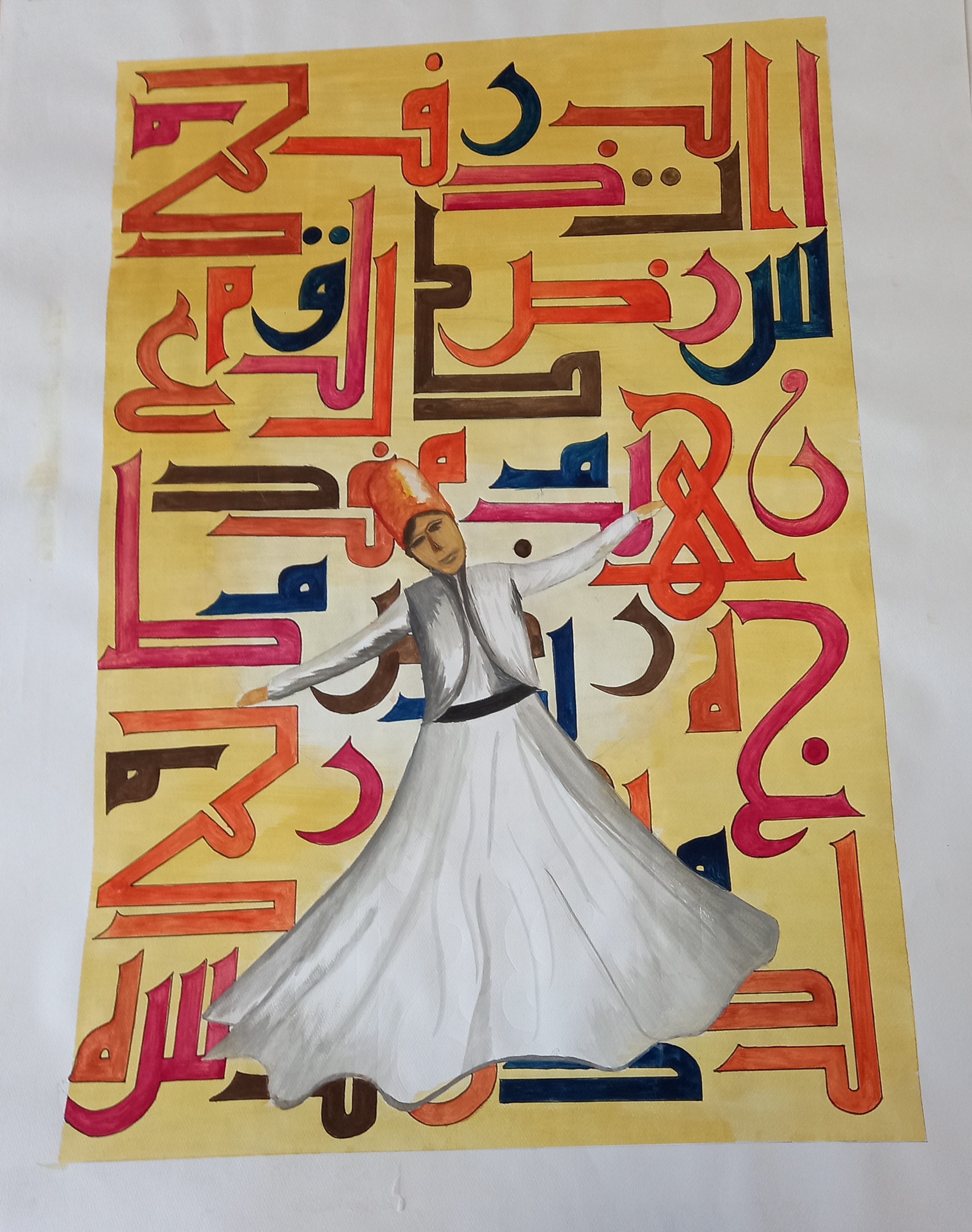

Islamic Art is intimately tied to the Divine Revelation, fusing truth and beauty as the same. The role of Islamic Art, according to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, is not just to provide a historical understanding of art, but to mold the soul of the artist. Taking the example of calligraphy, we can liken the calligrapher to the reed pen, where one needs to empty themselves just as a hollow pen for the Divine to flow through. The ink itself is a metaphor for the latter. In Islamic origin myth, the first thing that God created was qalam (pen). The writing holds a paramount significance in Islamic cultures. Throughout the centuries, Muslim scribes and calligraphers perfect the art of writing. In premodern Muslim societies, it was elementary learning aimed at grounding students firmly in the art and sciences of letters. The calligraphy was perceived as a spiritual exercise to cultivate perfect proportions within a soul as a reflection of divine unity. In addition to its artistic and spiritual dimensions, calligraphy became an integral aspect of the bureaucratic rationality of Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal courts. Designed as an experimental course for Habib University students, Divine Proportions fuses thought and action, perception, and practice into a single class taught by an anthropologist, Dr. Noman Baig, and a calligrapher, Ustad Kashif Khan. Drawing on ethnographic and traditional learning methods, students will explore writing in a broader context. The students explore the formation of Islam art, the phenomenology of creative practice, iconocity in religious visual culture, and epigraphy on tombstones. Furthermore, the course seeks to inspire students towards beauty – one of the fundamental tenets of Habib University’s core concept of Yohsin. It also fulfills a Liberal Core requirement of Creative Practice.

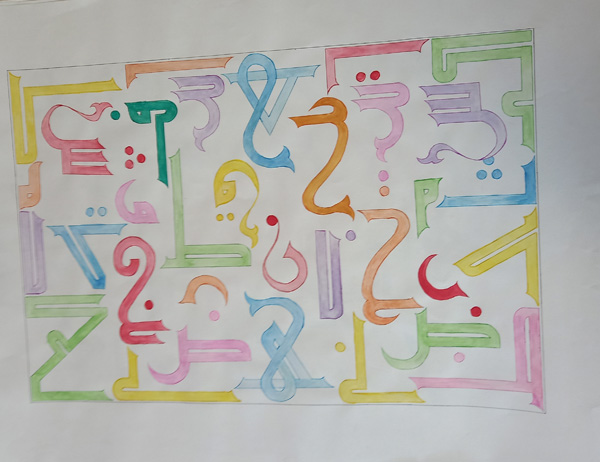

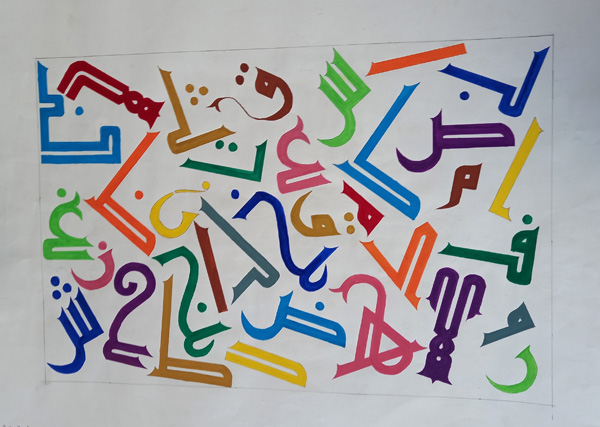

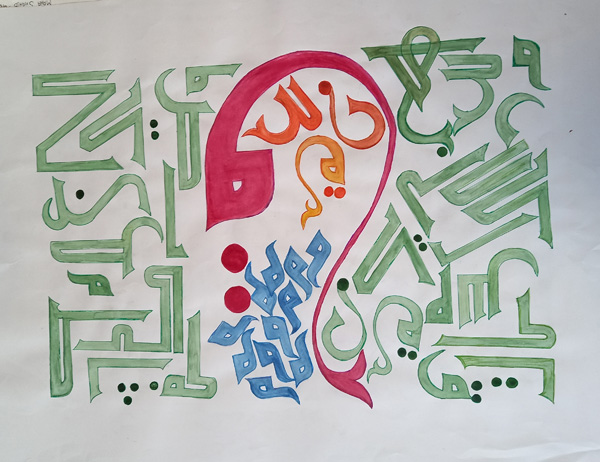

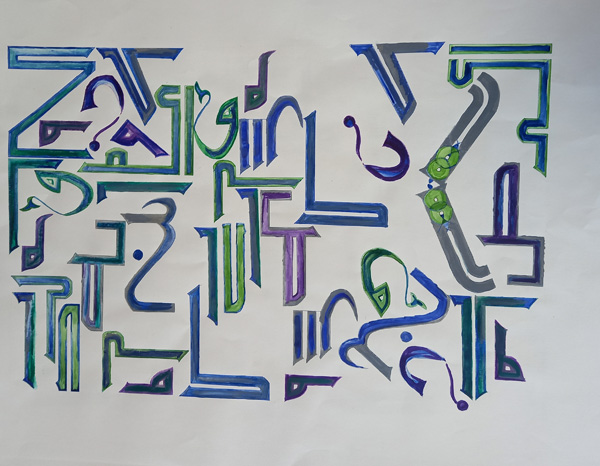

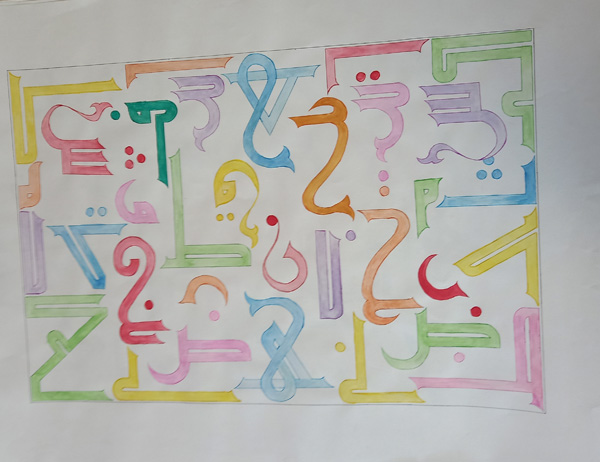

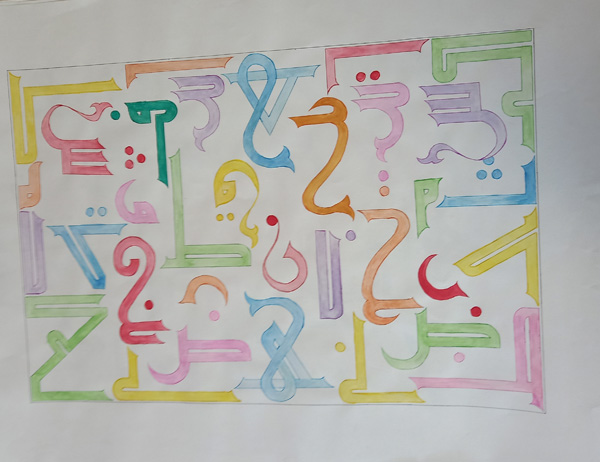

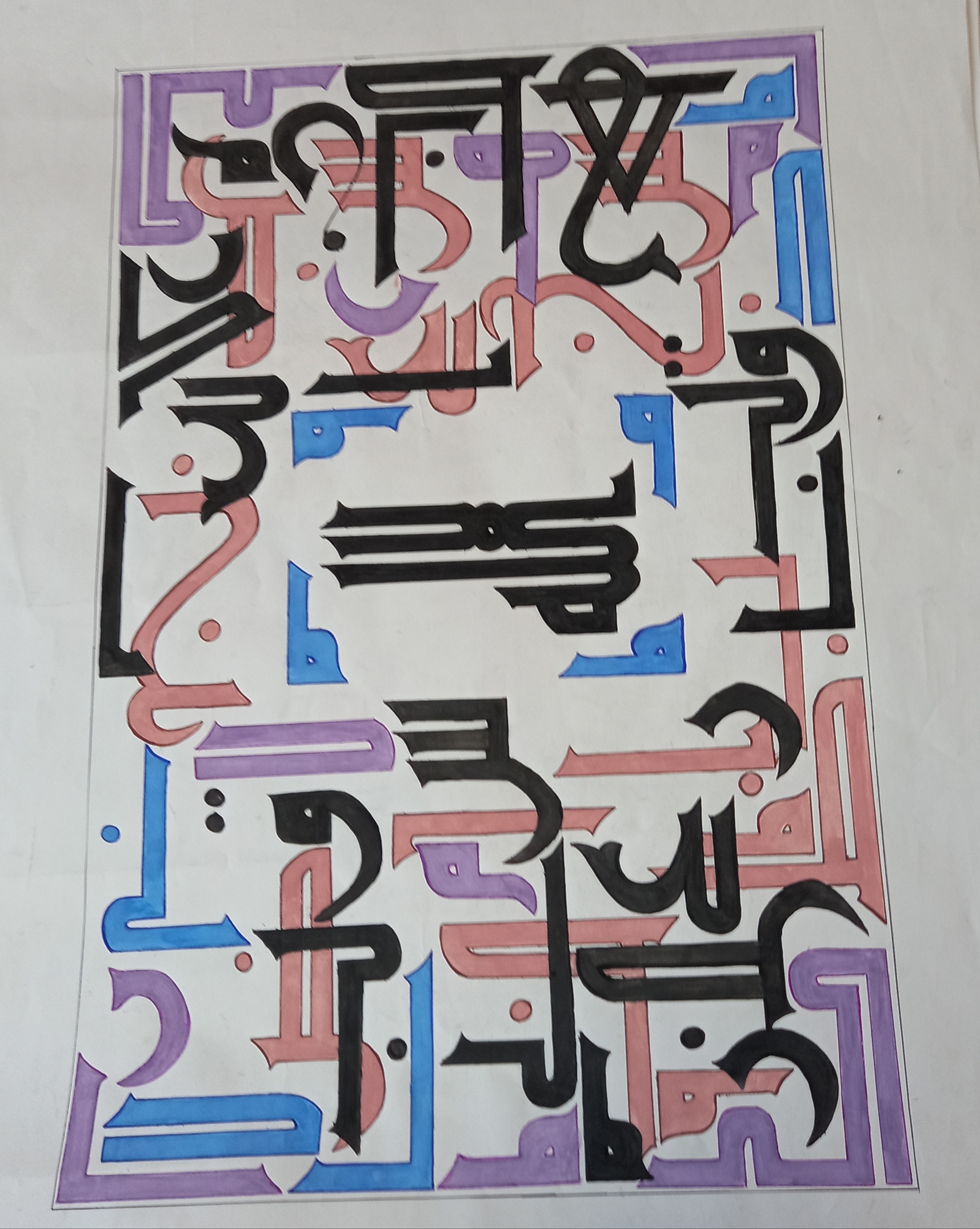

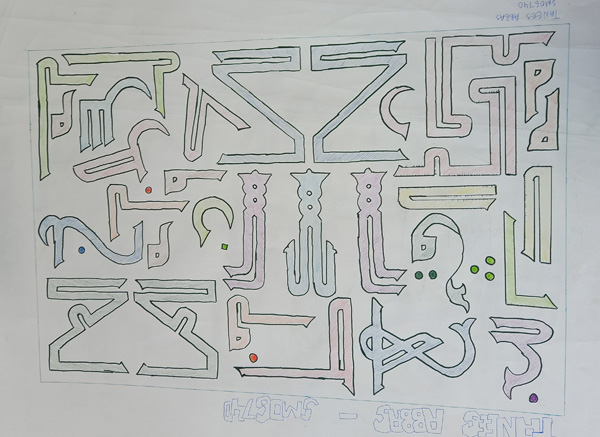

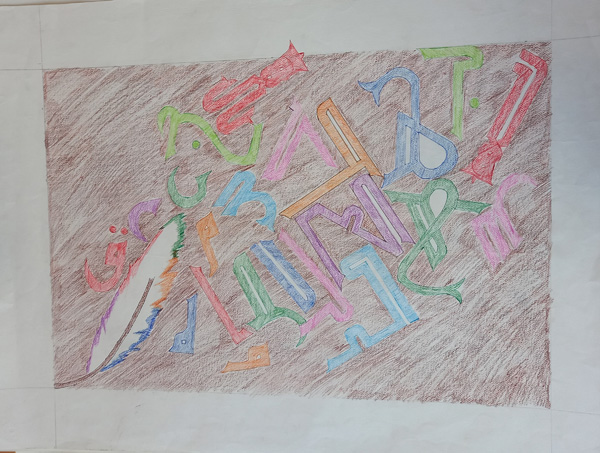

Calligraphic Letters

Abeeha Iqbal

Alina Baig

Asra Asim

Eisha Ahmed

Eisha Ateeq

Imra Rahim Hemani

Jannat Zeeshan

Maha Shahid

Mahnoor Farid Khan

Muniza Javed Qazi

Naveen Shariff

Rameen Irfan

Alifiya Fahim Lotia

Habab Idrees

Sana Khan

Luluwa Lokhandwala

Shahwaiz Gilani

Rida Fatima

Sabika Noor Ali

Samana Batul

Syeda Dua Zehra Zaidi

Tanees Abbas

Zobia Parvez Sharif